East Asian Observatory Deputy Director Jessica Dempsey says she is confident Hawaii has the highest concentration of women working as astronomers anywhere in the world.

But even with 73 women astronomers, by her count, employed across research institutions, that number still probably doesn’t exceed 30 percent of the workforce, Dempsey noted. That’s a figure she’s hoping to change.

“We still have a lot of work to do,” she said, in regard to increasing the number of women scientists.

For her, that got started in earnest Friday when she organized an event celebrating female astronomers at the ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center ahead of International Women’s Day, which is today.

Dempsey, 39, said there were 110 women who work for the Maunakea Observatories or supporting agencies in attendance, including scientists, engineers and administrators. At the event, 12 copies of a book about extraordinary women in science were presented to the state librarian to be distributed to Hawaii Island libraries.

She said the event was held to bring together women who make research on the mountain possible. But Dempsey also wants to extend that circle to include girls on the island who have an interest in science and help connect them with mentors who can encourage them to reach for the stars.

She wants to help create a new “generation of ferocious girls.”

“Everyone kind of assumes gender equity is going to happen passively, and we’ve actually shown that’s not true,” Dempsey said. “You have to force it. There’s a critical mass that you get to. Suddenly things do start to be self-generating, but we’re not there yet.”

She said it’s important for young women to have mentors as they enter male-dominated fields. And she sees an opportunity because of the number of women scientists in Hawaii who can provide that support.

“I personally believe the future of Maunakea should be held in the hands of the young people of these islands,” Dempsey said. “And I think that half of these future leaders of the cultural, scientific, spiritual and environmental preservation of this special place should be women.

“I have met an incredible array of young bright girls here in the school system, and I really want to provide the opportunity for them to be the ones to step up and have the opportunity to be leaders and define where that future goes.”

Dempsey said a mentoring program could be done through or complement the observatories’ existing outreach programs, such as Journey Through the Universe and Maunakea Scholars, the latter of which gives Hawaii high school students telescope time.

“You can say you have this community, these mentors, these role models,” she said. “And you can look at these people and say, ‘Hey, I can do that.’ To me, that’s the most important part of this.”

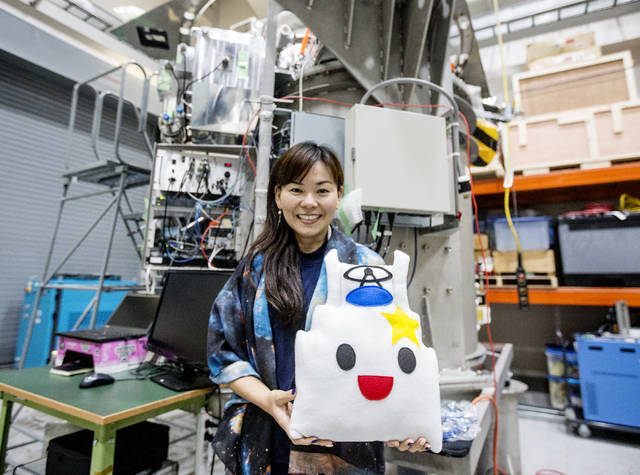

That’s something Yuko Kakazu, an astronomer and public outreach specialist with Subaru Telescope, fully supports.

She said women often feel like they have to work harder when they are underrepresented in a field or degree.

“I think a lot of women tend to get discouraged” from pursuing science, Kakazu said, noting that’s an issue that can start in grade school if they don’t have enough role models.

While they find many supporters in the field, Kakazu and Dempsey said gender bias can occur in subtle or unintended ways, including how men speak to women. But the toughest experience they had to overcome occurred in college. For both, it also became their greatest source of inspiration.

Kakazu, 40, said a professor in Japan told her she should not pursue a physics degree because she is a woman.

“That actually made me decide to major in physics,” she said.

Dempsey, who is from Australia, shared a similar story.

In response to a question she had after a physics class, she said a lecturer patted her on the head and “consoled me by saying, ‘Don’t worry about that. Women aren’t really capable of understanding the hard sciences. It’s not your fault.’”

“I turned around and said, ‘Right. I’m going to do this,’” Dempsey said. “But not everyone is as contrary as me. For a lot of people, that would be very discouraging.”

Even if a student doesn’t face gender discrimination that blatant, Kakazu said it’s important to have a strong support network and not give up on something you enjoy doing.

“There are always people who will support you if you try,” she said.

Laurie Rousseau-Nepton, a resident astronomer at Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, said support from friends and family helped her get through college, where she was one of the few women in her classes.

“The thing is, you put on your shoulder a lot of pressure to perform because you don’t want to disappoint anyone because you are the only one,” she said.

But that’s not a problem at CFHT, where Rousseau-Nepton said women astronomers are in the majority.

“You do feel a little different when people are used to working with women,” she said.

Rousseau-Nepton, 31, also was the first indigenous woman to receive a doctorate in astrophysics in the Canadian province of Quebec, where she is from.

She said her experience as an astronomer overall has been “absolutely positive.”

“I kind of feel like we’re following in the steps of other women who probably had a much more hard experience,” Rousseau-Nepton said. “I mean, I’m working with women who are from the older generation, and they have done a lot for us.

“I can tell we’re at this point because they worked for us to be there, and I want us to continue working in that direction because there’s still a lot of work to do.”

Email Tom Callis at tcallis@hawaiitribune-herald.com.